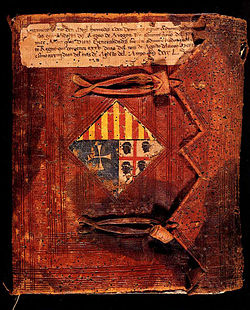

Diputación del General del Reino de Aragón

The Diputación del General del Reino de Aragón, Diputación del Reino de Aragón or Generalidad de Aragón was an Aragonese institution in force between 1364 and 1708 whose function was the representation by the estates of the realm of the Kingdom of Aragon in periods between Cortes before the King of Aragon and the rest of the peninsular kingdoms. It was in charge of intervening in internal and external fiscal, administrative and political affairs and of safeguarding and ensuring compliance with the aragonese Fueros.

The Diputación General de Aragón was an institution of permanent power whose origin was in the urgency of Peter IV of Aragon to raise funds in the face of the economic needs caused by the War of the Two Peters (1356–1369), for which convened in 1362 the Cortes in Monzón to the kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia and the Catalan principality. In its beginnings, the Diputación del General responded to the same fiscal functions as the Catalan and Valencian Generalidades of the same name, born of the collection purpose established from the creation of the tax of the Generalities, which began to be applied in Aragon from the Cort held in Zaragoza in 1364.

However, the institution soon became a key body for the management of the resources dedicated to the defense of the Kingdom, with administrative, political, military and representative attributions of the power emanating from the Cortes by delegation. It remained active uninterruptedly from the last third of the 14th century until the Nueva Planta decrees for Aragon and Valencia promulgated in 1707.

Eventually, it came to function de facto as the government of the Aragonese territory within the set of institutions of the Crown of Aragon until its dissolution. Before this collegiate body, the kings of the Aragonese Crown and, later, of the Spanish Crown, swore loyalty to the privileges and observances of the kingdom until the advent of the Bourbons after the War of the Spanish Succession.

It had its headquarters in the Palace of the Diputacion, or "Casas del Reino", a civil Gothic building located next to the Puerta del Ángel ("Angel's gate"), at the mouth of the Puente de Piedra, between la Seo and the Lonja de Zaragoza, constituting the political, economic, judicial and religious nerve center of the city and the kingdom. In its noble hall there was a gallery with the paintings of all the kings of Aragon and it housed the Archive of the Kingdom, which was partially destroyed after a dreadful three-day fire during the Sieges of Zaragoza, along with a large part of the palace. Some of the saved documents are preserved in the Archive of the Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza.[1] Another part is still missing and in private hands as an auction in 2017 brought to light.[2]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The Diputación del General del Reino de Aragón was born as a concession of the king to the Cortes convened in 1362 in Monzón in order to meet the economic and defensive needs caused by the war against Peter of Castile, known as the War of the Two Peters. To this end, he instituted the Generalidades that taxed the export of goods, in imitation of the existing in Catalonia, for the kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia and creating, in return, an independent representative body emanating from the power of the Cortes (who initially appointed their deputies), with fiscal powers called Diputación del General, known by antonomasia in the possessions of the monarch as "Generalidad".

Originally, its task was to collect the Generalidad tax—so called because it was universal and affected all the estates, including the king himself—and to administer it in order to defend the Kingdom and its Fueros. The tax affected the manufacture of fabrics, foreign trade and, from 1364 onwards, also imports and the sisas on basic necessities.

Although the tax was soon (from 1364) opposed by the branch of the cities, communities, towns and places (branch "of the universities") and the nobility, who felt aggrieved, the Cortes of Caspe, Alcañiz and Zaragoza of 1371–1372, already after the peace with Castile, would strengthen the institution by guaranteeing the representation and mediation function of these estates before the king and thus being able to defend their own interests in the periods between Cortes.

Thus, to the powers of administration of Hacienda and defense management are added those of political representation and intervention in all kinds of matters concerning the Kingdom and the defense of its own laws: Fueros, Libertades and Observancias. In addition, the reigns of John I (1387–1396) and Martin I (1396–1410) saw the decline of the Cortes, which met only three times during this period to deal with matters that otherwise did not deal with important policies. Thus, the Diputación del General or Generalidad gradually became the effective governing body for Aragonese affairs in terms of domestic and foreign policy.

The splendor of the 15th Century[edit]

With the advent of the Castilian dynasty of Trastámara after the Compromise of Caspe of 1412, the royal authority increased against the power of the Cortes. However, the Diputación General de Aragón was strengthened due to the prolonged absence of Alfonso V of Aragón, who moved his court to the Kingdom of Naples, and his lack of interest in the politics of the Hispanic territories of the Crown. So much so, that in the Cortes of Alcañiz of 1436 gathered by Alfonse V to ask for help in the delicate situation in Italy, he had to cede to the Diputación the representation of the Kingdom and the capacity to intervene in political matters of the utmost importance. The Generalidad also obtained the liberation from dependence on the Cortes, the body that until then elected its members, to institute a new election process through the appointment of members of the four branches of the estates by a complex procedure of sortition.

To elect the deputies, a procedure was established as of the "reparo" (or reform) of 1436 by which the names of the representatives of each of the social classes entitled to be elected were placed in two bags for each branch (richmen, ecclesiastics, knights and infanzones, and universities or civic branch), without indicating their dignity or position, according to the distribution of the attached table. Then, the innocent hand of a ten-year-old child proceeded to extract a wax ball or redolino containing the name of the elected representative, making a total of eight deputies whose mandate was annual.

| Ecclesiastical branch | Branch of nobles or richmen | Branch of knights and infanzones | Branch of universities representatives of cities, villages and comarcas |

|---|---|---|---|

Archbishop, Castellan of Amposta, bishops, abbots, priors and commanders. |

The eleven highest ranking lineages of the Aragonese aristocracy. |

Forty-one representatives of the nobility. |

Forty-seven "honest" leading and influential citizens of the capital of the kingdom. |

Members of cathedral and collegiate cabildos. Sixty representatives of ecclesiastical chapters. |

Fifteen second nobles of the aristocratic lineages or nobles de natura in the promotional phase. |

Formerly called "squire". Eighty representatives of the lower nobility. |

- Cities pool 67 candidates drawn at random with the following distribution: Huesca, Calatayud and Tarazona: 10 per city. Teruel: 9. Albarracín: 8. Daroca and Jaca: 6. Barbastro and Borja: 4. - Villages pool 44 candidates drawn at random with the following distribution: Monzón: 9 representatives. Tamarite: 7. Alagón and Fraga: 5 for each village. Alcañiz and Montalbán: 4. Sariñena: 3. Aínsa, Almudévar and Magallón: 2. - Communities pool 37 candidates drawn at random with the following distribution: Community of towns of Calatayud: 13 representatives. Community of towns of Daroca and Community of towns of Teruel: 12 each. |

In the second half of the 15th century, and until the reign of Ferdinand II of Aragon, the Diputación del Reino was responsible for maintaining order, settling disputes between the different estates and controlling the institution of Justicia by appointing his lieutenants. The king could not promulgate laws without the consent of the Cortes, or in its absence, of the Diputación, and the monarch had to swear that the measures approved by the Diputación would be applied and their compliance monitored by this permanent institution. In this way they became an element of independence from the Crown that was respected until the economic and political needs of the expansion of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries forced the king to intervene directly in the decisions of the Kingdom and finally impose his authority over its institutions.

Already King Ferdinand II, in his centralizing eagerness, implanted in Aragon the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and appointed in 1482 the Catalan John Ramon Folc IV, Count of Prades, Cardona and Pallars and trusted man of the king, as Lieutenant General of the Kingdom, giving rise to what is known as the Foreign Viceroy Lawsuit, since only a native of the kingdom could hold the position of Lieutenant General. In addition, and although he could not introduce the figure of the corregidor as was done in Castile, he reduced the independence of the branch of the universities by appointing the list of candidates according to the loyalty to his person, who, on the other hand, reserved the possibility of ordering the revision of the elective procedure. The cities, in exchange for accepting the appointment of the candidate by the king, received improvements in administration, trade and the granting of credits.[3]

All these measures were effective instruments of consolidation of the royal command to the detriment of the Diputación, although both the institution and the Cortes maintained their privileges without Ferdinand the Catholic undertaking any structural reform, which would not occur until 1592, after the outbreak of the conflict of powers with Philip II.

The conflicts of competence of the 16th century[edit]

The decline of the effective power of the Generalidad was accentuated with the arrival to the throne of Carlos de Gante, since the Aragonese deputies recognized his mother Joanna I of Castile as queen, and claimed that she should swear the fueros, libertades, uses and customs of the kingdom before her son, who should do it, during his mother's lifetime, as prince. One of the embassies sent by the deputies was even detained by order of Charles I. The conflict was only appeased after the intervention of Antonio Agustín, Vice-Chancellor of the Council of Aragon (the father of the well known polygrapher) accepting the formula of a simultaneous corregnate of Charles and his mother.

This episode was to be a preview of the continuous tensions that arose in the 16th century between the conflicting spheres of power of the monarch and the jurisdiction of the General of Aragon. The conflict of competences would become visible with its most acute crisis: the alterations of Aragon of 1591, in which Philip II made the imperial army intervene after the rebellion of the Aragonese government when it considered outrageous the detention in the Palace of the Aljafería, seat of the Inquisition, of Antonio Pérez, former royal secretary, who, by virtue of his Aragonese ancestry, invoked the Charter of this kingdom before the order of capture that weighed on him.

The reprisals of Philip II towards the Generalidad were very hard, executing one of his deputies, Juan de Luna and arresting two others. In addition, on February 8, 1592, the king suppressed the powers of the Diputación in matters of Defense and Guarda del Reino, which ensured the security of trade routes and border control. He also ordered the seizure of the acts of the Diputación and demanded reparations consisting of returning the income used in the call to raise an Aragonese army that could oppose the imperial troops, valued at 700,000 jaquesa pounds, an amount that left the kingdom in debt. From now on, the Diputación del General would not be able

to summon any city, village, or place in the Kingdom to meet (...) without the express wish of His Majesty, unless it is for matters concerning the Generalidades (...).

That is, for the original function of administration of Hacienda for which the institution was created in the 14th century. This "reparo" was ratified in the Cortes of Tarazona. From then on, the Diputación could not dispose of the collection obtained from the Generalidades tax, limiting itself to being a mere element of the administration.

The 17th century: the decadence of the institution[edit]

From then on, the Diputación was concerned with keeping alive the flame of the institutions and the existence of a ruling class in Aragon, manifested in an enormous work of legal and historical literature on the peculiarities of the region. Thus, since 1601, the Archive of the Kingdom of Aragon was organized and the writing of historical works was promoted by the Chroniclers of Aragon, among which Lupercio Leonardo de Argensola with his Información de los sucesos de Aragón de 1590 y 1591, en que se advierten los yerros de algunos autores... ("Information on the events of Aragon in 1590 and 1591, in which the errors of some authors are noted...") and the work of his brother Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola, Alteraciones populares de Zaragoza del año 1591 "Popular alteraciones of Zaragoza in the year 1591", written to counteract the Philippine version of the events; or the Anales of Juan Costa and Jerónimo Martel, eyewitnesses and chroniclers of the Kingdom, which were nevertheless destroyed by the royal censorship.

The Diputación also undertook the cartography of the kingdom, entrusted to the Portuguese Juan Bautista Lavaña and Ceremonial y breve relación de todos los cargos y cosas ordinarias de la Diputación del Reino de Aragón ("Ceremonial and brief relation of all the charges and ordinary things of the Diputación del Reino de Aragón"), by its Lieutenant Warden, Lorenzo Ibáñez de Aoiz. Both works were completed in 1611. On the other hand, the Diputación ordered to burn the Historia de las cosas sucedidas en este Reyno ("History of the things that happened in this Kingdom") in six volumes by the Castilian Antonio de Herrera because "in said Chronicles many things contrary to the truth were said" and Vicencio Blasco de Lanuza was entrusted with the writing of Historias eclesiásticas y seculares de Aragón ("Ecclesiastical and secular histories of Aragon"), whose second volume, which dealt with the serious events that had recently occurred, was published in 1619, three years before the first, which gives an idea of the intention to respond to Herrera's vision.

Throughout the 17th century, and from the reign of Philip III, the Diputación was reduced to a task of collaboration in arms, men and economic resources to the pressing demands of the Hispanic Monarchy and the centralizing project of the Union of Arms, especially from 1640 after the Uprising of Catalonia and Portugal. The urgency of the needs of the Imperium led the monarchy of Philip IV to bypass the foral procedures on numerous occasions without the Diputación being able to oppose due to the special war situation and the scarce power that the Aragonese institution could wield in the mid-17th century in the face of these outrages.

From these years onwards, Aragon collaborated to the best of its ability with international politics and for territorial integrity in the service of the policy of the Count-Duke of Olivares. The Aragonese contribution, however, was decreasing in consonance with the economic weakness that the Kingdom suffered in this century, which is reflected in the figures of its contributions to Spanish politics. In 1626 a service of 144,000 pounds a year was established to contribute to the Union of Arms and in 1640 an extraordinary congregation of the Diputación was able to contribute a levy of 4,800 men for three consecutive years who were engaged in the defense of Aragon in the face of the Franco-Catalonian advance. However, in 1678 it had difficulties in raising a service of 56,412 jaquesan pounds for the maintenance of two tercios of 750 men. In 1687, the service had to be reduced to 33,500 pounds per year and only one tercio. Suffice it to say that by 1650 the town of Caspe (one of the richest and largest in the Kingdom) owed more than 230,000 pounds in various concepts. The immense burdens that the Habsburg policy required were much greater than those that an impoverished Aragon, despite its willingness to collaborate, could maintain.

The expenses were charged to the Generalidades tax, after the ordinary expenses of paying officers and other services of the Administration of the Kingdom, that is to say, the surplus dedicated from the beginning to the financing of the defense was used. Well, in that year of 1687, the deputies, in order to collect the more than thirty thousand jaquesan pounds, had to levy a new tax on tobacco and salt leases. In 1693, after the invasion of Catalonia by the French army, the Deputation could not even gather a third of combat of 600 infantrymen, which was less than two hundred men, so Charles II asked for an effort to Branch of the Universities, that is to say, to cities, towns and communities, to complete the third with the contribution of an armed man for every fifty neighbors, without being able to be carried out given the state of prostration to which the Aragonese populations had arrived at the end of the 17th century. In 1698, the Consistorio, having exhausted all its resources, wrote to the king:

that this year being the Kingdom, due to the calamity of the times, with extreme sterility of all kinds of fruits, the ports, Universities and individuals are unable to make new contributions, and moreover, the voluntary donations of these years having been so repeated that some Universities have contracted new obligations because of them, which have yet to be paid.

After the power of the institution had languished, exanimated before the effort demanded by the constraints of the politics of the last Austrias, the institution would see its definitive end when it aligned itself during the War of the Spanish Succession with the pretension to the throne of Archduke of Austria, crowned as Charles III in June 1706 in Madrid. On the last day of that month all the deputies proclaimed Charles as king of Aragon in a solemn public act, with the only opposition of Miguel de Sada y Antillón, who fled to the Kingdom of Navarre, bastion of the House of Bourbon. In 1707, the pretender Charles III granted the deputies of Aragon the title of Grandes de España on an equal footing with that enjoyed by those of the Castilian consistory, but, after the Battle of Almansa in April 1707, the new king Philip V declared "abolished and repealed all the aforementioned fueros, privileges, practices and customs hitherto observed in the aforementioned kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia" in the Nueva Planta decrees. The Diputación del General del Reino de Aragón was definitively dissolved between January 11 and February 15, 1708.

Recovery attempts. The Diputación General de Aragón of the democracy[edit]

Since 1708, there have been several attempts to recover the institution as the governing body of Aragon. After the Bourbon reform, the collection functions of the extinct Diputación were taken over by the Junta del Real Erario, composed of two representatives from each of the former estates of ecclesiastics, nobles and universities (citizens).

At the beginning of 1808, in a reaction of a foral character against the Napoleonic invasion, the Cortes were reinstituted for a short time, which in turn created a Junta (with similar attributions to the Diputación) composed of three members from each of the traditional branches.

Later, with the Liberal Triennium (1820–1823) a Diputación Provincial de Aragón was again created under the Constitution of 1812 in May 1821, which was the first precedent of the Diputación Regional de Aragón provided for in the draft statutes of autonomy of 1931 and 1936 (known as Statute of Caspe), and which had continuity in the current democratic Diputación General de Aragón.

After the Franco dictatorship, on October 30, 1977, the preliminary draft of the Royal Decree-Law of Provisional Autonomy of Aragón was approved, which provided for a Diputación General de Aragón as the executive body, whose name alluded to the historical institution of government.

Once the document of the pre-autonomic regime for the Autonomous Community of Aragon (RDL 8/1978 of March 17) was approved, article three of it established:

The Diputación General de Aragón is hereby established as the governing body of Aragón, which shall have full legal personality in relation to the purposes entrusted to it.

Four years later, with the approval on August 10, 1982 of the Aragon Statute of Autonomy was definitively established with the highest legal rank as the executive parliamentary body of the Government of Aragón, which has since then completed several legislatures under the framework established by the Spanish Constitution of 1978, so that, without forgetting the past, the institution has performed the functions of the autonomous government up to the present day.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Archivo de la Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza". Potal DARA-Medieval.

- ^ "Denuncian la subasta de legajos del Archivo del Reino de Aragón robados tras el incendio de 1809". Diario ABC. 14 September 2017.

- ^ John Lynch, Monarquía e Imperio: el reinado de Carlos V, Madrid, El País, 2007, pág. 40 (Historia de España, 11).

Bibliography[edit]

- ARMILLAS VICENTE, José Antonio, La Diputación del Reino de Aragón, Zaragoza, Caja de Ahorros de la Inmaculada, 2000. ISBN 84-95306-47-6.

- — y SESMA MUÑOZ, José Ángel, La Diputación del Reino de Aragón. El gobierno aragonés, del Reyno a la Comunidad Autónoma, Zaragoza, Oroel (col. «Aragón cerca»), 1991.

- BITRIÁN VAREA, Carlos, Lo que no (solo) destruyeron los franceses. El ocaso del palacio de la Diputación del Reino de Aragón, Zaragoza, Institución Fernando el Católico, 2005, ISBN 978-84-9911-322-7.

- CANELLAS, Ángel, Instituciones aragonesas de antaño: La Diputación del Reino, Zaragoza, Diputación Provincial-Institución «Fernando el Católico», 1979. OCLC 23779872

- SESMA MUÑOZ, José Ángel, «Las Generalidades del reino de Aragón y su organización a mediados del siglo XV», Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español, XLVI, Madrid, 1976, págs. 393–467.

- —, La Diputación del Reino de Aragón en la época de Fernando II, Zaragoza, Institución «Fernando el Católico», 1977.